When the AI got it wrong: A real hospital’s wake-up call about medical LLMs

Imagine this scenario, not because it has happened, but because it inevitably will:

*This is a composite scenario based on documented LLM failure modes and real-world risk patterns. While no specific incident is cited, the risks are well-established in research.

Nothing seemed unusual. The patient, a 67-year-old man recovering from a cardiac event, was due to be discharged with follow-up instructions, lab reports, and medication guidance auto-populated by a new AI-powered assistant, part of the hospital’s push to modernize documentation with a large language model.

But something went wrong.

Buried in the summary was a subtle error: the model listed an outdated anticoagulant regimen no longer recommended after a medication switch noted earlier in the chart. No one noticed. The resident copied, pasted, and signed off.

Three days later, the patient was readmitted, this time with bleeding complications.

The promise of LLMs without the reality check

In this scenario, the hospital had deployed its medical LLM with great expectations. Based on a leading open-source model fine-tuned on biomedical text, it was marketed as “clinical-grade.” The rollout was fast-tracked under pressure to reduce clinician burden, improve documentation quality, and move the institution into the AI era.

There were no malicious actors. No regulatory violations. Just a quiet mistake, easy to make, easy to miss.

But in medicine, “quiet” does not mean harmless.

The post-mortem revealed a deeper issue: the model was not “hallucinating” in the traditional sense. It simply failed to account for longitudinal context. It did not “know” that a medication was recently discontinued because its memory window was too short to include earlier chart notes. It pulled information from a different encounter.

The AI had not failed its prompt. It had failed the patient.

How stress-testing might have prevented the error

This was not a cautionary tale about AI gone rogue. It was a lesson in what hospitals must do before they trust AI in clinical settings.

Had the hospital run structured stress-tests before going live, it might have caught the problem:

If these three specific layers had been integrated into the workflow, the failure would have been prevented at multiple stages:

First, a pre-deployment simulation using long, complex patient records would have identified the model’s context window limitations. This would have alerted engineers that the model was “losing” data at the beginning of lengthy files.

Next, a human-in-the-loop (HITL) validation pass would have served as a critical final check. This clinical review would likely have caught the outdated medication entry before it ever reached the final discharge note.

Finally, post-inference logging would have provided a clear audit trail. This transparency would have helped the team trace the model’s decision path, revealing exactly how it mistakenly pulled data from a medical encounter six months earlier.

The hospital did not yet have these systems. It had focused on model performance in demos and ideal use cases, not real-world messiness.

Building trustworthy AI starts with engineering for failure

This scenario isn’t far-fetched. Across the industry, health systems are under pressure to implement LLMs but often lack the infrastructure, oversight, and stress-resilience engineering to do so safely.

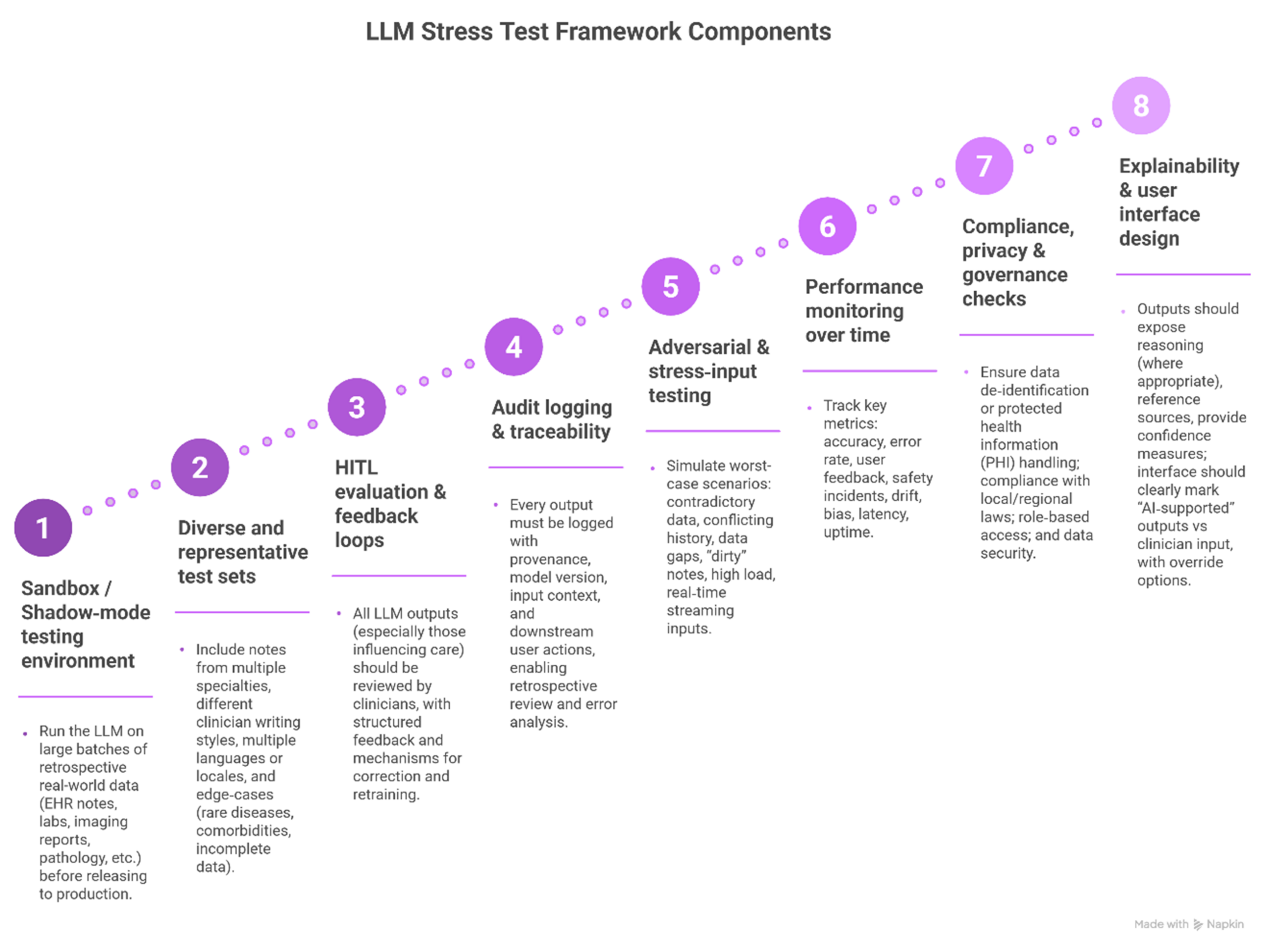

That is why organizations are now building LLM stress-testing frameworks that include:

- Sandbox environments simulating live workflows with messy data and diverse edge cases.

- Human-in-the-loop feedback that blends AI speed with clinician judgment.

- Governance layers that log every output, source, and downstream action for traceability.

- Real-time monitoring of model drift, hallucination rates, latency, and clinician override patterns.

These are not luxury features. They are the minimum viable safety system for AI in healthcare.

How John Snow Labs helps hospitals avoid this fate

At John Snow Labs, we have seen the pattern before. That is why our ecosystem is designed not just for performance, but for production:

- Generative AI Lab enables full-lifecycle orchestration: data ingestion, pipeline chaining, human-in-the-loop feedback, logging, and versioning.

- Our Medical Reasoning LLM is tuned for long-context understanding, reducing the risk of short-window misreads like the one in this story.

- Auditability and explainability are built-in from the start, so clinicians can trace and override model decisions with confidence.

- Our deployments include sandboxed evaluations, adversarial testing, and real-world performance monitoring as standard practice.

Hospitals working with us don’t just “try LLMs.” They implement safe, monitored, stress-tested medical AI pipelines they can trust because their patients cannot afford experiments.

Conclusion: Every LLM makes mistakes. What matters is what happens next

The question is not whether an AI system will make an error. It is whether the hospital is ready when it does.

Will the system catch the error before the patient is harmed? Will the log show what went wrong? Will the clinical team have tools to understand and improve the integration of the model in real clinical workflows?

In the new age of AI-driven healthcare, hospitals do not just need smart algorithms. They need resilient, accountable, stress-tested systems that operate safely under pressure, at scale, in the real-world.

FAQs

Q: Isn’t this just a rare edge case?

A: No. These kinds of subtle context errors are common when LLMs face long, messy, or shifting clinical records. Without stress-testing, they are hard to detect until potential harm occurs.

Q: How can a hospital run a stress-test before going live?

A: Use de-identified historical data in sandbox mode. Feed complex cases into the model. Simulate full workflows. Log and analyze outputs. Engage real clinicians for review.

Q: Are LLMs safe for high-risk clinical decisions?

A: Only with safeguards. With proper validation, auditability, human oversight, and governance, LLMs can become safe components of clinical workflows, but never unsupervised decision-makers.